Jo Panuwat D - stock.adobe.com

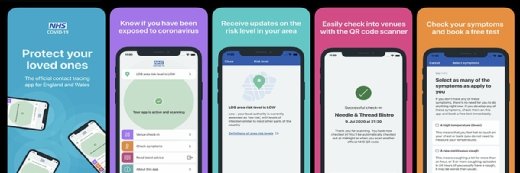

Why UK needs independent oversight body for contact-tracing app

The public needs and deserves clarity, and not just assurances, over the UK’s Covid-19 contact-tracing app

It is no secret that the development of the UK’s Covid-19 contact-tracing app – due to be launched in the coming weeks – has been controversial. Like many governments around the world, the UK is looking to deploy a contact-tracing app as part of a broader strategy for lifting its lockdown.

Unlike other European governments, however, the UK has thus far resisted using the technological tools being offered by Google and Apple in favour of its own proprietary solution involving a centralised database controlled by the UK’s Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC).

The NHS believes its approach achieves a proper balance between individual privacy and the protection of public health, although that view appears increasingly in the minority compared with the rest of Europe. After a brief, glitch-ridden trial in the Isle of Wight involving nearly 70,000 residents (or roughly 50% of the local population), the NHS believes the app is ready for a broader deployment across the UK on a voluntary basis.

Today, most contact-tracing apps being considered in Europe rely on our smartphones to monitor the individuals with whom we have been in close proximity, using Bluetooth technology and according to parameters – such as distance and time period – set by app developers.

Centralised versus decentralised

The apps tend to fall into one of two broad categories – centralised models and decentralised models. In Europe, this divergence is mirrored in the competing efforts of the Pan-European Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing (PEPP-PT) initiative, seemingly aligned with the former approach, and the Decentralised Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing (DP3T) initiative, aligned with the latter. Discussions between the two sides have become increasingly acrimonious in recent weeks, and European lawmakers, privacy regulators and other key stakeholders have weighed in as well.

Notwithstanding concerns expressed by privacy advocates and positions taken in countries such as Ireland and Germany, the UK has opted for a centralised model with its NHS Covid-19 app. When a registered user becomes infected and updates their status via the app, the user’s phone sends its own unique device identifier and the identifiers of those devices with which it has come into contact to the DHSC centralised server, along with the time and duration of contact. The centralised server then conducts the “contact matching” process and sends alerts to any individuals deemed to be at risk, encouraging them to self-isolate or take other appropriate steps.

By contrast, in any decentralised model, the infected individual’s phone only uploads his or her own device identifier, leaving phones rather than a central server to determine the contact matches. As a consequence, this model both enhances the privacy of users of the relevant app by limiting the information collected centrally, but also denies public authorities, or other parties, the ability to mine the data derived from app usage for epidemiological, clinical and other purposes.

According to statements published by the NHS, the additional data it will gather – time of incident, signal strength, duration of contact, and half of each user’s postcode – will be used to map the spread of the virus, help hospitals prepare for new patient waves, and learn about what types of interactions carry the greatest risk. The massive pseudonymised dataset – a dataset that uses artificial identifiers – could also assist in training artificial intelligence (AI) to more accurately determine which individuals should be self-isolating.

These relative benefits, however, must be viewed in light of the privacy risks they present. There is an unfortunate and recognised public policy trade-off between the ability to use such data to control or predict future outbreaks and generate other data of interest, versus the threat that this data could later pose to individual privacy should it fall into the wrong hands.

According to the NHS contact-tracing app’s data protection impact assessment (DPIA), the greatest privacy risk concerns false symptom reporting, both innocent and malicious. Although subjecting an individual to quarantine unnecessarily has severe rights implications, there are also more issues at stake in terms of personal privacy.

Anonymous data could be re-identified

The NHS contact-tracing app provides the government with access to each user’s social network – a map of their relationships and interactions. And, because this is personal data, it is not, legally speaking, anonymous. With the adoption of additional measures (placing a sensor on an Oyster card reader, for example) or adding additional app functionality (offering clinical testing, for example), the UK government could, if it so wished, identify users of its app. Meanwhile, future research endeavours and analysis of the data will inevitably add to the re-identification risk – something conceded in the app’s privacy notice.

To its credit, NHSX, the NHS digital innovation unit that developed the app, has been transparent that additional features could be added and that users may be asked to volunteer their highly sensitive location data in the future. This risk of “feature creep” is particularly pronounced, however, where data is controlled centrally, making it vital that the NHS adheres to data minimisation and purpose limitation principles – preventing it and others from using data in ways unforeseen by users. All of this assumes, moreover, that app users would be adequately informed and competent to offer up valid consent.

In the meantime, the potential vast quantity of pseudonymised contact data, the potential ability for UK government bodies to cross-reference this with other personal data, and the lack of clarity as to what personal data will eventually be collected, how it might be used and shared in the future, and when it will be deleted, is naturally causing anxiety for many.

Unanswered questions

But the list of concerns continues and the public needs and deserves clarity, and not just assurances. This includes clarity as to: the nature and legal basis of public-private data sharing agreements, the app’s automated decision-making (the risk-scoring algorithm, for example) and the Bluetooth handshake mechanism; the extent of the technical limitations associated with using the app on Android and iOS and its interoperability with other apps across borders; why users cannot exercise their right of data erasure and data access; how the server-side code supporting the app functions; the effect of digital exclusion; and how the NHS will prevent malicious users forcing mass notifications or compromising the server.

Though the list is substantial, the issues do not appear to be a reflection of mal-intent on the part of the NHS. The efficacy of the app depends on public trust, and aware of the criticism and concern, the NHS is following in the footsteps of Germany by developing a second app in parallel that relies on the Google and Apple contact-tracing application programming interfaces (APIs). This willingness to adapt is a positive indication, but calls for clarity are now likely to be amplified.

Specific primary legislation to regulate the app and a new, truly independent oversight body would certainly be a welcome development and help ease concerns, but in light of the overly positive picture painted by the DPIA, this seems unlikely to manifest. With the app launching imminently, answers in any form would be welcome.

Dan Cooper is a partner at Covington & Burling LLP.