Olivier Le Moal - stock.adobe.co

NSO Group faces court action after Pegasus spyware used against targets in UK

Three human rights activists whose phones were targeted by spyware traced to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have begun legal action against both countries and Israel’s NSO Group Technologies

The Israeli company behind Pegasus spyware, NSO Group Technologies, faces the prospect of legal action in a British court after Pegasus was used against the mobile phones of targets in Britain.

Lawyers have sent pre-action letters to NSO and the governments of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia claiming that Pegasus was used to spy on human rights activists in the UK.

The case, which represents the first time that the Israeli firm faces the prospect of legal action in a British court, comes amid growing concern about the misuse of Pegasus spyware by governments.

This week, the Citizen Lab disclosed that Pegasus spy software linked to the United Arab Emirates was used in a suspected attack against 10 Downing Street.

Multiple attacks linked to Pegasus operators in the UAE, India, Cyprus and Jordan also targeted the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in 2020 and 2021, the Citizen Lab said.

Pre-action letters

Separately, law firm Bindmans has filed pre-action letters against NSO Group Technologies, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia on behalf of three people in the UK involved in sensitive human rights work.

Anas Altikriti, a prominent political advisor and hostage negotiator, Mohammed Kozbar, chairman of the Finsbury Park Mosque, and Yahya Assiria, a pro-democracy campaigner, claim that their mobile phones were hacked in the UK.

They are seeking to bring claims against NSO Group Technologies and the UAE and Saudi Arabian governments in the High Court for breach of privacy.

The three claimants are part of a larger group of activists, academics, politicians and other prominent figures, represented by Bindmans and the Global Legal Action Network, a non-profit organisation that pursues legal action across borders.

Monika Sobiecki, partner at Bindmans, which is crowdfunding the case, said she expected to bring two further legal claims from people who were targeted in the UK, including one who was hacked multiple times.

NSO Group Technologies, which denies the claims, is accused of breaching the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the misuse of private information, harassment and trespass to goods.

The three claimants have also issued legal letters against the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, which have so far not responded to the allegations.

Mining phones

NSO Group Technologies sells its spy software to governments, which can use it to infect iPhones and Android phones.

Pegasus is capable of extracting and recording all information on the phone, including text messages, contact lists, passwords, browsing history, phone calls and the geographic location of the phone.

Pegasus can also be used to remotely turn on a camera and microphones on an infected phone, effectively turning it into a bugging device, and to bypass encryption in messaging services such as WhatsApp or Signal.

According to the legal letters, NSO has supplied Pegasus to states with poor human rights records. The spyware has been used against human rights defenders, lawyers, journalists and political dissidents.

Mohammed Kozbar

Mohammed Kozbar, community leader and chairman of the Finsbury Park Mosque, has publicly opposed the actions of the United Arab Emirates, and is associated with well-known critics of the regime.

Kozbar learned last year that his phone number appeared in a leaked list of 50,000 phone numbers identified as potential targets of Pegasus.

Forensic analysis by the Citizen’s Lab’s Bill Marczak confirmed that Kozbar’s phone had been infiltrated by Pegasus in February 2018, in an attack linked to the UAE.

The phone contained confidential information relating to Kozbar’s work, his contacts, private messages to family members and confidential information about his health.

Anas Altikriti

Anas Altikriti, founder of the Cordoba Foundation, is a vocal critic of the Emirates regime who has criticised the UAE’s targeting of political dissidents and opponents.

He has spoken out against the “normalisation” agreement reached between Israel and the UAE in August 2020, describing it as a “shameful pact” and an abandonment of the “legitimate struggle of the Palestinian people for their undeniable basic rights”.

Altikriti was targeted by Pegasus software linked to the UAE while taking part in a sensitive hostage negotiation in the UK in July 2020.

Forensic analysis by Amnesty International and the Citizen Lab confirmed that data had been extracted from Altikri’s phone by the spyware.

Within weeks of the hacking, Altikriti’s contact with the victim and alleged kidnappers suddenly stopped.

Information appeared in articles published in various languages that appeared to contain confidential information about his contacts and work, which Altikriti believes were unlawfully taken from his phone.

He is concerned that individuals he was in contact with subsequently disappeared as a result of information obtained by the UAE from his phone.

Yahya Assiri

Yahya Assiri, who fled to the UK in January 2014, is a prominent Saudi dissident who has publicly criticised the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s human rights practices.

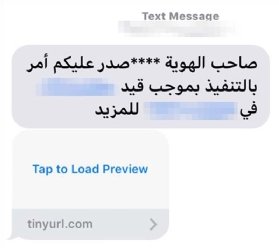

Assiri received a text message in July 2020 containing a link to Pegasus internet domains that matched previous attacks on Saudi dissidents.

Analysis by the Citizen Lab confirmed that his devices were infected with Pegasus in July 2020, followed by a further attempt two weeks later.

At the time of the attack, Assiri was working on the case of murdered journalist Jamal Khashoggi, advocating sanctions on Saudi officials and lobbying for a UK boycott of the Saudi-hosted G20 summit.

Assiri had stored a large volume of sensitive and confidential information on his iPhone, including court documents, details of contacts, ID documents of human rights defenders in Saudi Arabia, along with other highly sensitive information.

Saudi Arabia’s “potential acquisition of this data was and is nothing short of catastrophic for the claimant and his contacts”, the legal letter states.

Assari argues that NSO must have known about Saudi Arabia’s human rights record, including the criminalisation of dissent, unfair trails, torture and execution.

The Khasoggi connection

The Israeli government temporarily delayed an export licence for NSO to supply Pegasus to Saudi Arabia following the murder of US-based journalist, and critic of the Saudi regime, Jamal Khasoggi in the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul.

Amnesty International found evidence that Pegasus was present on Khashoggi’s fiancée’s phone four days after his murder by Saudi agents.

Khasoggi’s son and other family members in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates were also selected for targeting.

Can UK courts hear claim against Israeli company?

The case brought by the three claimants will test whether courts in England and Wales have the jurisdiction to hear a case against the Israeli company.

Bindmans’ Sobiecki said there were strong grounds for the case to be heard in a court in England and Wales.

“The balance falls largely in favour of the claimants. They were very much in the UK at the time of the hacking and two out of three of them are UK citizens,” she said.

The three individuals bringing the legal claims against NSO were initially identified on a leaked list of potential Pegasus targets.

The list was obtained by the Pegasus project, an international coalition of journalists, coordinated by Forbidden Stories with technical support from Amnesty International’s Security Lab.

London technology firm Reckon Digital carried out forensics imaging and analysis of infected phones to support the legal action brough by the three activists.

Reckon Digital analysed multiple devices for signs of infection by hooking the phones up to a laptop running published computer scripts written by Citizen Lab and Amnesty International.

“The idea was for us to be the people doing the work in the UK on digital imaging and collecting data from physical devices,” said Reckon Digital director Fabio Natali.

Analyst Orange Clay said most of the hacking attempts only appeared to have lasted for a few days. “In general, it seems to be based around certain events or when there is something of interest happening,” he said.

Clay made forensic copies of the data before passing them on to Bill Marczak, senior research Fellow at Citizen Lab and researcher at UC Berkeley (California), for further analysis.

NSO claims ‘state immunity’

NSO argued in a response to the legal letters that UK courts have no jurisdiction over NSO, which is based in Israel, and that legal action is barred by “state immunity”.

The company also argued that there was no proper basis for showing that NSO acted as a “data controller or a data processor” under UK data protection law.

There is no basis to claim that NSO joined in a “common design” with Saudi Arabia or the UAE that would make it “jointly liable” with the two countries, it said.

NSO said it provides surveillance software for the “exclusive use” of state governments and their intelligence services.

It claimed to pride itself on being the only company in this field “operating under an ethical governance framework that is robust and transparent”.

The company said it had policies in place to ensure its “products would not be used to violate human rights”.

It claimed that the legal letters repeated “misinformation” from reports and statements by non-governmental organisations, including Citizen Lab, Amnesty International and Forbidden Stories.

“We have repeatedly confirmed that NSO licenses it Pegasus software only to states and state authorities for licensed purposes,” it said.

It said that customers are required to provide declarations under Israel’s Defence Export Control Law that they will only use Pegasus for the prevention and investigation of terrorism and criminal activity.

NSO argued that although it licenses Pegasus to customers, it does not operate Pegasus and has no access to information on how it is used or to its customers’ data.

“NSO accordingly has no knowledge of the individuals whom states might be investigating or the plots they are trying to disrupt,” it said.

The company said servers and nodes used by Pegasus to communicate are not owned by NSO, but by its customers.

There is no suggestion, “nor can there be”, that the acts complained of were carried out by Pegasus in England.

It argued that the case should be heard in Israel, under Israeli law.

Property damage

Sobiecki said there were exceptions to state immunity for property damage and personal injury.

That will be tested in an ongoing legal case brought by law firm Leigh Day on behalf of Ghanem Al-Masarir, a vocal opponent of the Saudi regime, who was also targeted with Pegasus.

UK Pegasus attack

Citizen Lab researchers found that Pegasus was used to infect a device connected to a network at 10 Downing Street on 7 July 2020.

The Citizen Lab suspects that the United Arab Emirates was behind the hacking attempt based on the servers.

According to a report by Ronan Farrow in the New Yorker, the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) tested several phones at Downing Street, including Boris Johnson’s, but was unable to find the infected device or to identify what data may have been stolen.

Phones linked to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) were hacked on at least five occasions between July 2020 and June 2021.

As the FCO, and its successor the Foreign and Commonwealth Development Office, has staff in many countries, the suspected infections could have related to FCO devices located overseas and using overseas SIM cards, said Ron Diebert, director of the Citizen Lab, in a statement.

“The United Kingdom is currently in the midst of serval ongoing legislative and judicial efforts relating to regulatory questions surrounding cyber policy, as well as redress for cyber victims. We believe that it is critically important that such efforts are allowed to unfold free from the undue influence of spyware,” he said.

A former employee of NSO told the New Yorker that NSO had remote access to its customers’ software and to the data they collect, contradicting public claims by the company.