everythingpossible - stock.adobe

NHSX contact-tracing app needs legislative oversight

Legal experts have told Parliament’s Human Rights Committee that legislation is desirable to ensure public trust in the data security of the Covid-19 coronavirus contact-tracing app

NHSX’s Covid-19 coronavirus contact-tracing app – which will move into a beta testing phase on the Isle of Wight imminently – could benefit from additional legislation in order to safeguard data security and enhance the general public’s trust in using it, Parliament’s Human Rights Committee has heard.

At a remote Zoom hearing on the afternoon of 4 May 2020, chaired by Labour’s Harriet Harman, Orla Lynskey, associate professor of law at the London School of Economics (LSE), and Micheal Veale, lecturer in digital rights and regulation at University College London (UCL) expounded on the need for some kind of legislative oversight.

“I think that legislation here would be desirable for different reasons,” said Lynskey. “A lot of the principles are set out in the data protection framework, however they are quite flexible, so it would be useful to be transparent to the public as to how those principles will be applied.

“The introduction of the app raises issues beyond data protection and privacy, such as whether or not individuals may find themselves compelled to produce the app, or to download it. That is beyond the role of the Information Commissioner, and goes into areas of human rights and discrimination.”

Veale said: “We need a roadmap of where this is going, who might have access, and without that roadmap and accountability around it, it is very hard to say the system is secure against mission creep.”

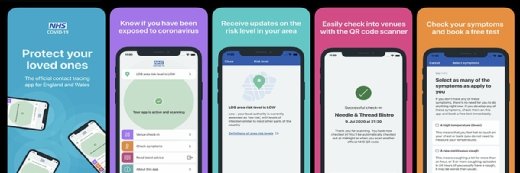

The app will work by logging the distance between a user’s phone and others nearby who have also installed it using the Bluetooth Low Energy standard. It will store a log of proximity information on the device, using a randomised number linked to the device. It will not know your name, who you have been near, or where you have been.

NHSX chief executive Matthew Gould said: “It gives every app user a rotating, randomised identifier. If I have the app, it doesn’t know me as Matthew, it knows me as a number. Then, if I become ill, I have the choice to allow the app to upload this information, and that, in turn, triggers notifications that the NHS can send anonymously to other app users I’ve been in contact with.”

Gould stressed that people do not have to give up their personal information to use the app, although they will be asked to enter the first half of their password (for example, W1), which the NHS could use to help identify coronavirus hotspots.

“We have put privacy at the heart of the app and how it works,” said Gould. “It is designed so that you don’t have to give it your personal details. The app is voluntary. You need to choose to download it, enable it, and you need to choose to upload your data if you become symptomatic.”

Gould added that there would be a legal commitment that the data will be deleted after the crisis has passed. “We are trying very hard to do the right thing in the right way,” he said.

Veale, however, highlighted concerns over who is allowed to access the data generated by the app and warned that different social groups may have different perceptions as to how secure the data is, depending on who has access to it.

It was very easy, he said, to say that only the NHS or the Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC) could see it, but it did not necessarily follow that the Investigatory Powers Act, for example, could not be used by another department to gain access to it – for example, by the Home Office for the purpose of immigration enforcement.

Read more about contact-tracing apps

- BCS and Cass Business School call for proposed UK contact-tracing app not to be launched without alignment to testing.

- Leading UK scientific experts assure MPs that much-anticipated contact-tracing app will be ready for launch in May, but concede that challenges exist on achieving meaningful uptake.

- Singapore’s Government Technology Agency contributes the source code of the BlueTrace protocol that powers its contact-tracing app.

- Australian government launches Coronavirus Australia app to keep people updated on the latest developments in fight against coronavirus outbreak.

- Telecoms will play a key role in controlling the coronavirus through contact-tracing apps that can mitigate its spread, but only if people actually use the apps – and that’s not guaranteed.

Veale also highlighted that the centralised nature of NHSX’s system – whereby the data is sent to, and controlled at, a central server – was of concern from a human rights and privacy perspective.

In this type of system, he said, although the randomised numbers are only supposed to be used to contact nearby devices, they could still be decrypted into a form that allows the originating device to be singled out. The data could then be used to identify clusters of friends, families, employees, political activists, and so on.

Veale added that while the numbers may appear random, to anyone controlling the central repository, the numbers will be the same. So if someone controlling the server saw a number and either remembered it or wrote it down, they could identify it again, and gain the ability to track a subject’s device.

Veale proposed an alternative, decentralised system, which is what several other European countries, including Ireland, are proposing.

In a decentralised system, the basic functionality would work much the same, the difference being that if one user was to develop Covid-19, instead of uploading the random identifier to the NHS server – a potential point of failure – it would transmit it to devices it had been near, so that they can instruct those people on what to do next, without any central server being involved.

Veale said there would be a trade-off in terms of less data being available to the NHS, but this would also have the effect of reducing the possibility of mission creep.