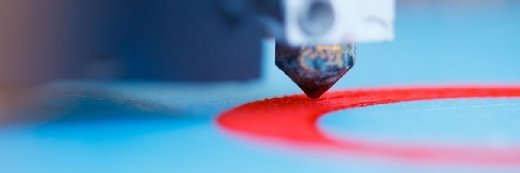

nikkytok - Fotolia

3D printing gets serious in the Netherlands

3D projects abound in the Netherlands, with the technology being applied to canal bridges, bicycles, ship components and buildings

The hype surrounding 3D printing started a few years ago, but is now quietening down. Gone is the buzz surrounding pioneers, innovators and investor darlings such as MakerBot, Ultimaker and the Dutch “poster child” of 3D printing – Shapeways.

The expectation at the start of this decade was that 3D printing would unleash a home manufacturing revolution comparable to the DTP (desktop publishing) revolution that was made possible by the PC and 2D printers.

“You’ve heard of 3D printers, but you probably don’t own one yet,” wrote Wired in 2012. The comparison was made to early PCs – expensive, limited to techies, perceived as gadgets, but promising. Both had common origins as highly technical machines. And both were destined to evolve into user-friendliness and utilisation for non-technical, real-world work.

But the enthusiastic prediction that most homes would have a 3D printer has not come true. This is in stark contrast to PCs, and for a long time 2D printers. Those machines did appear “on every desk and in every home”, in line with the vision of Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates. But the fact that most homes don’t have a 3D printer does not mean there is no revolution.

3D printing is slowly emerging for business applications: in healthcare, in prototyping and manufacturing, in inventory and supply chains, for example. This adoption is taking place in industry, not in the home. Analysts see eight-fold growth for the 3D printing market over the next few years, from being worth $5bn worldwide now to $40bn in 2020 – and the Dutch want part of it.

Forget the 3D consumer market for now and take the industrial sector, which is currently picking up 3D printing. Look, for example, at Boeing’s new space taxi, the unmanned Starliner. The US aviation giant has hired a small company, Oxford Performance Materials, to make about 600 3D printed parts for its space programme. The parts are being made from special fire- and radiation-resistant plastics.

This is quite a leap from NASA’s 2014 production of a ratchet wrench on board the International Space Station. Boeing’s use of 3D printing for its Starliner is also space bound, but in the international harbour of Dutch city Rotterdam, 3D printing is being explored for seafaring ships. Last year, the Port of Rotterdam announced its Fieldlab additive manufacturing facility for the 3D printing of ship propellers.

The process is the same as regular 3D printing, but uses metal instead of plastic. The investment of several million euros into the Rotterdam Fieldlab follows a successful pilot in 2015.

Read more about 3D printing

- Manufacturing companies are looking into more and more ways to incorporate additive manufacturing. Here is a look at some of the reasons and ways 3D printing use is evolving.

- Because of their lightweight nature, 3D printed braces can help improve patient compliance in the group most affected by scoliosis – adolescent females.

- As 3D printing disrupts business and technology mandates, CIOs can gain new relevance as business enablers.

Metal is also the base material for two other Dutch 3D printing innovations – a futuristic bicycle and an artistic canal bridge in Amsterdam. The first project has already been completed. Students at the Technical University Delft printed a steel bike frame, which is just as heavy and usable as a regular frame. The Arc Bicycle, as it is known, was launched in April last year by Dutch minister of economic affairs Henk Kamp, who took it for a ride. The three-month printing process involved layering molten pieces of metal on top of each other – a process the makers describe as drawing lines in the air.

The creation of the Arc Bicycle was made possible by Dutch robotics company MX3D and its multi-axis robotic arms. The dimensions of traditional 3D printers restrict the size of objects they can output, but MX3D offers “printing outside the box”, said the company’s CTO, Tim Geurtjes.

This approach is markedly different from another Dutch project, 3D Print Canal House, designed by DUS Architects. This ambitious project aims to make a complete Amsterdam canal house, printed in parts that then need to be assembled. The 3D printer used for the project is a repurposed shipping container called the KamerMaker.

Meanwhile, MX3D is about to start another 3D printing project – a pedestrian bridge. Its 3D printing robots will build a canal bridge, metal drop by metal drop, to form a load-bearing mesh. This showcase innovation is planned for Amsterdam’s red light district. Since the scheme was announced in the summer of 2015, MX3D has been experimenting and refining the bridge, designed by Dutch artist Joris Laarman.

Spain appeared to have beaten the Netherlands’ scoop for the world’s first 3D printed bridge when a structurer was installed in a Madrid park last December. But the Spanish bridge was made from concrete, produced in eight parts and then assembled. The Dutch bridge will see the printing robots making the stainless steel structure as they cross it – meeting in the middle to finish the construction.

Watch the bridge grow

However, contrary to the initial plan – and mock-up photos – the printing will not be done live on location at the Oudezijds Achterburgwal, because although the bridge itself will be weather (and tourist) proof, the robots (and the construction process) are not. Instead, it will be done in MX3D’s studio in Amsterdam-Noord, where the public can come to watch the bridge grow. Production is scheduled to start during the first quarter of this year, and the bridge should be in situ in the red light district at the beginning of next year.

This 3D printing project may be a showcase, but it is also a sign of serious industrial interest in the Netherlands. One of the parties involved is venerable Dutch construction giant Heijmans, a 93-year-old company that is also taking part in the plastic printed 3D Canal House.

While that build will take about three years to complete, the possibilities for more custom construction and creative output are intriguing the Dutch, who see a third industrial revolution, merging digital with manufacturing.

The possibilities have also caught the Netherlands government’s attention. At the end of last year, the ministry of economic affairs unveiled an action plan for smart industry. Working with Dutch research and technology organisations, it aims to boost development and standards for smart industrial applications. This includes 3D printing, which is seen as an economic growth area.

The hip development area of Amsterdam-Noord is already home to an impressive mix of building styles – now 3D printing promises to break the mould for housing, bridges, bicycles, ship parts, and more.