CROCOTHERY - stock.adobe.com

UK comms experts continue to question contact-tracing app

Academics and comms industry experts challenge UK government scientists on their defence of NHS contact-tracing app, in particular the issue of centralised data gathering

The UK government may have earned some plaudits for attempting to use a mobile contact-tracing app to aid the fight against Covid-19, but the controversy over its nature, in particular its centralised database, is rumbling on.

On 4 May, the government, backed by leading experts in the UK’s epidemiology, IT and communications sectors, released more information on how the app – the first details of which were announced on 24 April – would work in its first scale trial on the Isle of Wight.

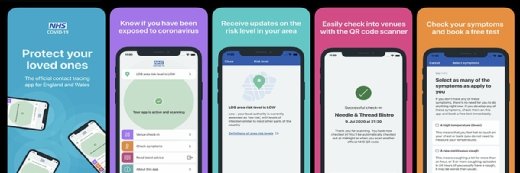

Developed by NHSX, the NHS’s digital healthcare innovation unit, the contract-tracing app works by using Bluetooth to automate the “laborious” process of contact tracing and has the goal of reducing transmission of the virus by alerting people who may have been exposed, so they can take action to protect themselves.

Once installed, the app will start logging the distance between a user’s smartphone and other phones nearby that also have the app installed using Bluetooth Low Energy. The anonymous log of how close users are to others will be stored securely on the user’s phone. If a user becomes unwell with symptoms of Covid-19, they can allow the app to inform the NHS which, subject to sophisticated risk analysis, will trigger an anonymous alert to other app users with whom the user came into significant contact over the previous few days.

Yet almost as soon as the first details of the app’s capability were announced, critics weighed in with concerns over what the app could achieve and whether the UK public could or would make representative use of it. In particular, the main bone of contention was whether the app’s centralised nature would lead to privacy breaches and also whether it would be of any use at all though lack of user uptake.

On 4 May, just as the official launch of the second phase of the app was getting under way on the Isle of Wight, the UK government came out fighting against the critics, with the nation’s pre-eminent scientists who were involved in the app’s creation defending it from the criticism of its effectiveness and the use of centralised data gathering.

In particular, they noted that the approach would lead to a big data set, so that the NHS could draw in all the information it needed to refine risk assessment, especially with regard to relaxing social distancing rules.

But anyone thinking that such defence would end the debate was wrong. Almost immediately after the Isle of Wight launch, and in assessing where the biggest challenge for the app would come from, Muttukrishnan Rajarajan, director of City University of London’s institute for cyber security, said that although several decentralised approaches have already been successfully implemented across the world for Covid-19 tracing, the UK app’s fundamental architecture, in which all the data management is controlled centrally, was “an obvious privacy issue.”

“Any centralised system is more vulnerable to cyber attacks, especially if they hold sensitive data,” said Rajarajan. “The main problem here is because of the involvement of the NCSC [National Cyber Security Centre] to validate the framework. This means the general public are fearful that government will be tracking and tracing our movements and will record all our location data.”

Rajarajan said there were several privacy techniques that could be used to overcome these privacy challenges. He noted that techniques such as homomorphic encryption would allow the user to have total control of their personal data and that programmers could design schemes based on such security to carry out the computation in the encrypted domain, so there was no data leak to government or third parties.

Read more about contact tracing

- UK scientific experts address doubts on UK contact-tracing app’s effectiveness, particular regarding data privacy, but admit that its nature may have to evolve as the roll-out scales up.

- Telecoms will play a key role in controlling the coronavirus through contact-tracing apps that can mitigate its spread, but only if population masses actually use the apps – and that’s not guaranteed.

- Singapore’s Government Technology Agency contributes the source code of the BlueTrace protocol that powers its contact-tracing app.

- Federal government launches Coronavirus Australia app to keep Australians updated on the latest developments in fight against coronavirus outbreak.

Digital economy security firm Approov said that from a privacy perspective, the UK app is actually an improvement on the approach adopted by Australia’s COVIDSafe app and Singapore’s TraceTogether app, from which the former is derived. These require a phone number during the signup process, so that contact tracers can get in contact if proximity to an infectious person is suspected.

However, in its analysis of the functional elements of the UK app, Approov said app users’ phones would be constantly open to transmitting identifiers, including an encrypted form of the app’s instance ID. It argued that anyone with access to the NHSX database, and thus the decryption key, would be able to know the instance ID of the device.

It pointed out that this also meant that even though the database does not contain the user’s identity, it would only take one event in the real world from, say, personal contact, a modified point-of-sale device or a face recognition system to associate the instance ID with the actual person’s identity.

Rajarajan said that as the app develops, there could be an interesting safety versus privacy trade-off, examining whether to compromise our safety over being over-cautious or even paranoid about privacy. “Once citizens feel the added benefits from the app to self-manage the Covid-19 situation and if they can be convinced that the data is never going to be stored beyond the current pandemic, I think we will all sign up to use this app,” he said.

“It will be a community-driven app. Early take-up may be slow, but once people see the added benefits and as we slowly move out of the lockdown phases, everyone will start to use this app to avoid a second peak of the virus. I think in situations like this, our safety will be our top priority.”